Global Perspectives on Generics: How Countries Are Cutting Drug Costs Without Compromising Care

By 2025, generic drugs made up over 90% of all prescriptions filled in the United States - but they accounted for just 23% of total drug spending. That’s the power of smart policy. Across the world, governments are using wildly different strategies to make medicines affordable, and the results aren’t always what you’d expect. Some countries slash prices so hard that manufacturers can’t stay in business. Others create quiet incentives that quietly boost competition. The goal is always the same: get life-saving drugs into people’s hands without bankrupting the system. But how they get there tells a much deeper story about health, economics, and power.

How the U.S. Keeps Generics Cheap - And Why It Still Has High Drug Prices

The United States doesn’t set drug prices directly. Instead, it lets markets negotiate - and it has one of the most powerful negotiators in the world: Medicare. Thanks to high generic use (90.1% of prescriptions) and aggressive bulk purchasing, public-sector drug prices in the U.S. are 18% lower than in other wealthy nations. The FDA approved over 11,000 generic products by the end of 2024, and the Competitive Generic Therapy (CGT) program speeds up approval for drugs with little or no competition. Zenara Pharma’s Sertraline Hydrochloride capsules, approved in August 2025, got 180 days of market exclusivity under CGT - enough to recoup costs before others enter. But here’s the twist: even with all those cheap generics, the U.S. still pays more for drugs overall. Why? Because the branded drugs - the ones still under patent - are priced at levels no other country tolerates. Generics hold down the average, but they don’t touch the high-end. A single course of a new cancer drug can cost $100,000, and Medicare has no power to cap those prices yet. That’s about to change. The Inflation Reduction Act’s drug price negotiation rules, fully active by 2028, will force manufacturers of 10-20 high-cost branded drugs per year to lower prices or lose Medicare access. Analysts predict a 25-35% revenue drop for those drugs - and that could push even more patients toward generics.Europe’s Price Puzzle: Identical Drugs, Different Costs

In Europe, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) approves generics for the whole bloc. But then - and this is the key - each country sets its own price. That creates a mess. A pill made in Germany, approved by the EMA, and sold in France might cost €0.15. The exact same pill, sold in Poland, might cost €0.50. In some cases, price differences between neighboring countries exceed 300%, according to the OECD’s 2025 Health at a Glance report. Countries like the Netherlands solve this by playing a game of external reference pricing. They pick a list of countries - France, Belgium, the UK, Norway - and then set their own prices lower than the lowest of those. It’s legal, it’s strategic, and it works. The result? Dutch patients pay less for generics than almost anyone else in Europe. Germany, on the other hand, uses mandatory substitution: pharmacists must swap a branded drug for a generic unless the doctor writes "do not substitute." That policy pushed generic use to 88.3% by volume. Italy, with no such rule, lags at 67.4%. The difference isn’t income or education - it’s policy design. The EU is trying to fix this with its new Pharmaceutical Package, expected in late 2025. It aims to harmonize reimbursement rules and give faster market access to the first generic that enters a market. If it works, it could cut generic entry times by 12-15%.China’s Volume-Based Procurement: The Nuclear Option

China didn’t try to negotiate prices one by one. In 2018, it launched Volume-Based Procurement (VBP) - a system where the government holds a single auction for each drug, and the lowest bidder gets to supply 80% of the country’s hospital demand. The catch? The winner has to sell at a price so low, many manufacturers operate at a loss. The results are brutal. Average price cuts hit 54.7%, with some drugs dropping over 90%. Amlodipine, a common blood pressure pill, went from $1.20 per tablet to $0.08. But there’s a cost. In 2024, 12 provinces in China faced a six-to-eight-week shortage of Amlodipine because manufacturers couldn’t make enough at the price they’d bid. The China Generic Pharmaceutical Association found that 23% of manufacturers were selling VBP drugs at negative margins. That’s not sustainable. China’s National Medical Products Administration (NMPA) has cut approval times to 10-12 months, but the real bottleneck isn’t regulation - it’s pricing. Manufacturers are caught between government pressure and shrinking profits. Experts warn this could lead to quality issues. The FDA issued 2,183 import alerts for quality violations in 2024 - up from 1,247 in 2020 - and many of those targeted Chinese and Indian plants.

India: The World’s Pharmacy, But With Quality Risks

India makes 20% of the world’s generic drugs by volume. It’s the go-to source for low-cost medicines across Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia. That’s thanks to Section 84 of the Patents Act 1970, which allows the government to issue compulsory licenses - basically, override patents - if a drug is too expensive or not available in sufficient quantities. But speed comes with risk. Indian manufacturers produce generics for over 150 countries. The Central Drugs Standard Control Organization (CDSCO) has cut approval times from 36 months in 2019 to 14 months in 2025. That’s impressive. But doctors on MedIndia Network report that 58% of them have seen inconsistent bioavailability in certain generics - especially for antiepileptics and blood thinners. One wrong dose can cause seizures or strokes. The FDA has increased warning letters to Indian generic makers by 17% between 2022 and 2024, citing data integrity issues. That’s not about corruption - it’s about pressure. When you’re forced to cut prices by 80% to win a contract, and your margins are already thin, cutting corners on testing becomes tempting. The Access to Medicine Foundation warns this could erode global trust in Indian generics - a dangerous blow to a system that supplies the world.South Korea’s ‘1+3’ Rule: Less Is More

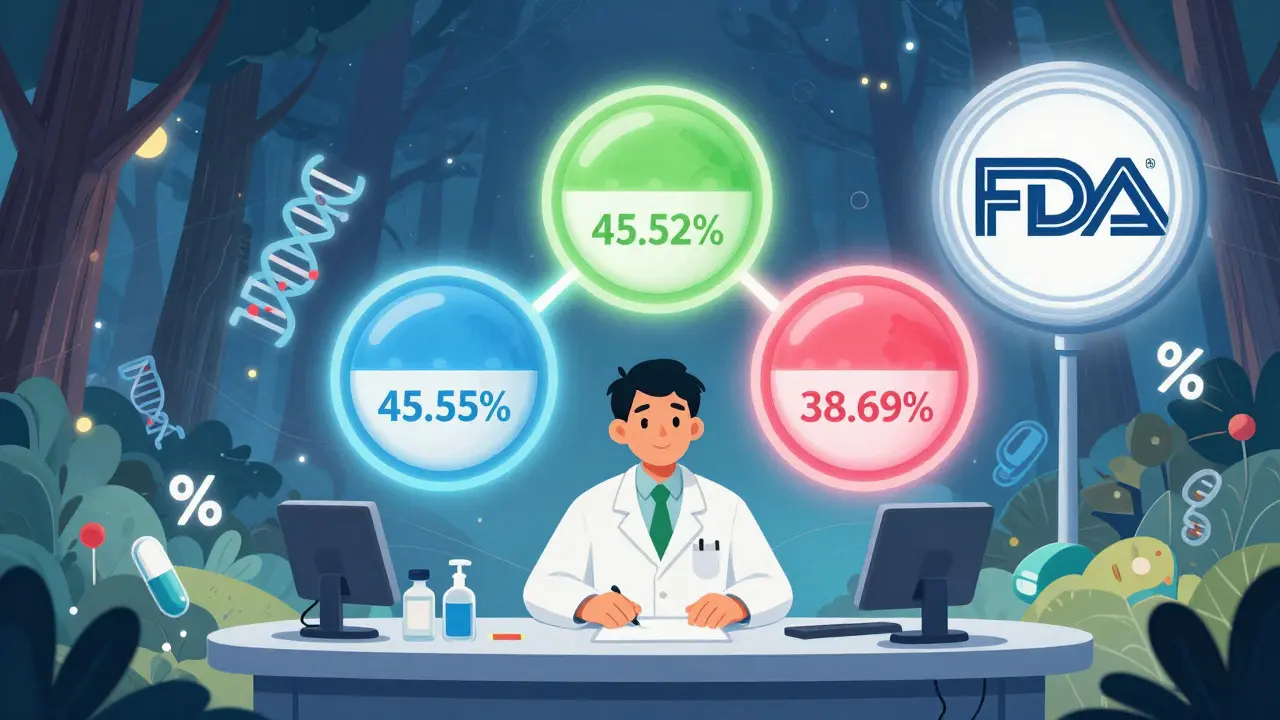

South Korea took a different approach. Instead of flooding the market with dozens of cheap generics, it limited entry. The 2020 ‘1+3 Bioequivalence Policy’ allows only three generic versions of a drug to be approved - and they all must use the same bioequivalence data as the first one. No more redundant testing. No more price wars between 15 nearly identical products. It worked. Between 2020 and 2024, redundant generic entries dropped by 41%. But there’s a flip side: new generic launches fell by 29%. Fewer companies entered the market because the reward wasn’t worth the risk. The government also introduced a Differential Generic Pricing System: generics that meet both quality and price standards get 53.55% of the brand’s price. Those meeting only one criterion get 45.52%. The rest? Just 38.69%. It’s a clever system - it rewards quality and punishes low performers. But it also slows competition. The Frontiers in Public Health 2025 study suggests this might be why South Korea’s generic market growth has flattened. Innovation isn’t dead - it’s just harder to enter.

What Works - And What Doesn’t

There’s no single formula for success. But some patterns keep showing up. What works:- Mandatory substitution (Germany, Netherlands)

- Clear bioequivalence standards (80-125% AUC and Cmax ranges)

- Physician and pharmacist education (boosts acceptance by 22-35%)

- Transparent pricing that leaves manufacturers with at least 15-20% gross margin

- Price cuts so deep they cause shortages (China’s VBP)

- Fragmented pricing that discourages cross-border trade (much of Europe)

- Over-reliance on low-cost manufacturers without quality oversight (India, some African markets)

The Future: Consolidation, Quality, and Global Standards

By 2030, the number of global generic manufacturers is expected to drop from 3,500 to around 2,200. Why? Because margins are collapsing. Only companies with integrated R&D, manufacturing, and global distribution can survive. Smaller players will be bought out - or go under. The biggest threat isn’t policy. It’s quality erosion. As prices drop, so does the incentive to invest in testing, stability studies, and clean manufacturing. The FDA’s rising number of import alerts is a red flag. The International Generic and Biosimilars Association (IGBA) is pushing for global bioequivalence standards. Right now, a generic approved in the U.S. might need full retesting in Brazil or Nigeria. If countries recognized each other’s approvals, generic entry could accelerate by 18-24 months in developing nations. That’s life-changing for people in low-income countries. The next decade will be defined by one question: Can we make drugs affordable without making them unsafe? The answer will shape global health for generations.Are generic drugs as safe as brand-name drugs?

Yes - when they’re made by reputable manufacturers and meet regulatory standards. Generic drugs must contain the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand-name version. They’re required to be bioequivalent, meaning they deliver the same amount of medicine into your bloodstream at the same rate. The FDA, EMA, and WHO all confirm that generics are therapeutically equivalent. The main risks come from poor manufacturing or inconsistent quality control - not the generic model itself.

Why do some people say generics don’t work as well?

Most of the time, it’s not the drug - it’s the perception. People associate lower price with lower quality. But in rare cases, especially with narrow therapeutic index drugs like warfarin or levothyroxine, even small differences in inactive ingredients or absorption rates can matter. In India and some emerging markets, inconsistent manufacturing has led to real bioavailability issues. That’s why physician education and pharmacist guidance are critical. If your doctor switches you to a generic and you feel different, talk to them - it’s not always in your head.

Why are generic drugs cheaper if they’re the same?

Branded drugs cost billions to develop, test, and market. Generics skip all that. They don’t need new clinical trials - just bioequivalence studies. They don’t spend money on TV ads or fancy packaging. They also face competition from multiple manufacturers, which drives prices down. In the U.S., 11,000+ generic versions of common drugs compete. In China, a single auction can drop prices by 90%. The savings come from eliminating duplication and leveraging scale.

Can I trust generics made in India or China?

Many are perfectly safe - and many are the backbone of global health supply chains. But quality varies. The FDA and EMA regularly inspect facilities in both countries. In 2024, the FDA issued over 2,000 import alerts for quality violations - many targeting plants in India and China. That doesn’t mean all products are bad. It means you need oversight. Look for generics approved by strict regulators like the FDA, EMA, or Health Canada. Avoid unregulated online sellers. If a generic is sold through your local pharmacy and approved by your country’s health authority, it’s almost certainly safe.

Will generic drug shortages get worse?

Yes - unless policies change. When governments force prices below manufacturing cost, companies stop making the drug. China’s VBP program caused shortages of Amlodipine and other essential medicines in 2024. India’s low margins have led to production halts. The WHO warns this threatens universal health coverage. The solution isn’t higher prices - it’s smarter pricing. Governments need to guarantee minimum margins (15-20%) to keep manufacturers in business. A reliable supply chain is more valuable than a 50-cent savings on a pill.

Mindee Coulter

January 28, 2026 AT 16:07Generics are the unsung heroes of modern medicine. I’ve been on them for years-blood pressure, antidepressants, you name it. Same effect, 90% cheaper. Why are we still acting like they’re second-rate? The stigma is ridiculous.

Anna Lou Chen

January 28, 2026 AT 16:47Let’s not romanticize the neoliberal fantasy of ‘market-driven affordability.’ The U.S. doesn’t have a pricing system-it has a rent-extraction architecture disguised as competition. Generics are merely the smoke screen. The real cost is externalized onto global supply chains, exploited labor, and compromised bioequivalence standards. We’re not saving money-we’re outsourcing risk.

The FDA’s 2,183 import alerts? That’s not regulatory rigor-it’s the sound of a system collapsing under its own structural contradictions. When profit margins dip below 15%, you don’t get quality control-you get corner-cutting, falsified data, and batch-to-batch variability. This isn’t capitalism. It’s predatory pharmacology.

And don’t get me started on India’s ‘14-month approval’ as a badge of honor. Speed without integrity is just acceleration toward catastrophe. The WHO’s 2025 guide is right: affordability without safety is a death sentence dressed in a discount coupon.

China’s VBP? A brutal but honest experiment in state capitalism. The shortages aren’t bugs-they’re features. When you force manufacturers into negative margins, you don’t get innovation-you get ghost factories. The real tragedy? We’re all complicit. We want cheap pills, but we refuse to pay for the infrastructure that makes them safe.

And yet… we still treat this like a technical problem. It’s not. It’s a moral failure wrapped in a spreadsheet.

Global bioequivalence standards? A noble idea-but only if we stop letting the U.S. and EU dictate them while ignoring the Global South’s lived realities. Who gets to define ‘bioequivalent’? Who funds the testing? Who bears the liability when it fails? These aren’t policy questions. They’re questions of power.

By 2030, we’ll have 2,200 manufacturers left. Who are they? The ones who bought the regulators. The ones who outsourced compliance to shell companies in the Caymans. The ones who turned generics into a commodity, not a right.

We need a new paradigm. Not more auctions. Not more reference pricing. Not more ‘smart’ policies. We need to treat medicine as a public good. Not a market. Not a commodity. A right.

And until then? We’re just rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic. While people die waiting for a pill that might not work.

Lexi Karuzis

January 30, 2026 AT 03:00Okay, but have you seen the FDA’s whistleblower reports? 😳 The data manipulation in Indian labs? The ‘phantom batches’ that never existed? The ‘retesting’ that was just copy-pasted from 2018? This isn’t just negligence-it’s systemic fraud. And guess who pays? US taxpayers. And you. And your grandma on Medicare.

And don’t even get me started on how the ‘1+3’ rule in South Korea is just a backdoor monopoly for Big Pharma’s preferred suppliers. It’s all connected. The FDA. The EMA. The WHO. All cozy with the same 12 manufacturers. It’s a cartel. A global drug cartel. 🕵️♀️

And now they want to harmonize standards? So we can all be equally fooled together? 🤡

Colin Pierce

January 30, 2026 AT 14:28Just wanted to add a real-world note: I work in a rural clinic in Ohio. We switched 80% of our scripts to generics 3 years ago. No increase in ER visits. No drop in adherence. Patients love it. The key? Pharmacist counseling. We sit down with people, explain why it’s safe, and even let them try one batch before switching full-time. Trust matters more than price tags.

Also-India and China make 80% of our generics. But the ones we get through CVS or Walgreens? FDA-approved. That’s the filter. Don’t buy from shady websites. Stick to pharmacies. It’s that simple.

Brittany Fiddes

January 31, 2026 AT 06:16Oh, please. The U.S. is the only country with the guts to let the market work. Europe? They’re just price-fixing cartels with better tea. Germany’s mandatory substitution? That’s state coercion. China’s auction system? Economic vandalism. And India? They’re the world’s pharmacy because they don’t care if you live or die as long as the order ships.

Meanwhile, the UK sits there with their NHS, pretending they’re ethical while importing 60% of their meds from plants that got flagged by the FDA last year. Hypocrites.

Generics aren’t the problem. Weak governments are. Stop outsourcing your healthcare to bureaucrats who think ‘affordable’ means ‘dangerous.’

John Rose

January 31, 2026 AT 12:09This is one of the most balanced takes I’ve read on generics. The tension between access and safety is real, and no single model solves it perfectly. But I’m hopeful. The Inflation Reduction Act’s negotiation rules? That’s the first real step toward fixing the branded drug crisis. And global recognition of approvals? Huge. If Brazil can accept an FDA-approved generic without retesting, millions get faster access. That’s progress.

Also-kudos to South Korea’s 1+3 rule. Sometimes less competition means better quality. We assume more options = better, but in pharma, it can mean more risk. Thoughtful restraint > chaos.

SRI GUNTORO

January 31, 2026 AT 16:20India is not a pharmacy. India is a lifeline. Over 1.5 billion people in Africa and Asia rely on our generics. Yes, there are bad actors. But 99% of our manufacturers follow the rules. The FDA’s alerts? Many are from small, unlicensed labs-not the big ones supplying the world. Don’t punish 100 million workers because a few cut corners.

We don’t have the luxury of 20% margins. We have patients who can’t afford $100 pills. If you want quality, fund it. Don’t shame us for existing.

Mark Alan

January 31, 2026 AT 20:35China just dropped amlodipine to 8 cents. 😱 That’s cheaper than a Starbucks coffee. But now people are dying because they can’t get it. 🤦♂️ So… which is worse? Paying $1.20 or not getting it at all? 🤔

Also, why does no one talk about how Big Pharma is secretly buying up generic companies to control supply? 🕵️♂️ It’s all connected. 🤫

Rhiannon Bosse

February 2, 2026 AT 03:54Let me get this straight: the U.S. lets Medicare negotiate generics but can’t touch branded drugs? That’s like letting your landlord fix the sink but not the leaking roof. 😂

And the ‘180-day exclusivity’ for Sertraline? That’s not innovation-that’s a loophole. One company gets to milk the market for half a year while everyone else waits. That’s not competition. That’s a monopoly with a waiting room.

And now they want to ‘harmonize’ global standards? Great. So we can all be equally exploited by the same 5 corporations? 🤡

Meanwhile, my cousin in rural Alabama is skipping her insulin because the generic version ‘didn’t work.’ She didn’t know it was a bad batch. She just thought she was ‘sensitive’ to generics.

This isn’t policy. It’s a horror movie. And we’re all in it.